Christina Kaululani Sun: Championing health, human security, and data access

How can we empower Indigenous and minority communities to collect, use, and communicate the results of their own data to improve health outcomes?

As a Native Hawaiian, or Kānaka Maoli, with mixed ancestry from the indigenous Cou (pronounced “Tsou”) tribe in Taiwan, Christina Kaululani Sun has been reflecting on this question for many years. Her pursuit of the answer has led her to an academic career at the intersection of epidemiology, data science, and climate justice.

As a Master of Public Health student in the Epidemiology—Global Health track, Christina splits her time between school and operating the UW Food Pantry, which provides resources for food-insecure students, faculty, and staff on campus. In this last year, she has worked to identify some of the barriers to accessing food in order to make the pantry shopping experience more welcoming.

“Having a permanent physical location close to public transit, for instance, meant we could expand our hours throughout the week to serve more people who live and work off campus,” she said. “We’ve also begun working with several partners, including the UW Farm, ASUW Student Food Cooperative, Housing & Food Services, and Starbucks, to redistribute healthy and nutrient-dense food to those needing supplemental nutrition.”

In the classroom, Christina has learned the methodologies needed to use data for the public good. With these new skills, she sought out research opportunities focused on improving the health outcomes of Indigenous and other non-dominant populations through data.

For her practicum experience last spring, Christina worked with the City of Tacoma on a project to address food insecurity for urban communities of color and immigrant populations through the creation of a food innovation district designed to also increase community engagement. The project would provide culturally appropriate foods in a centralized area for culturally and ethnically diverse populations in East Tacoma.

Christina and her team also evaluated sites and programs that could benefit from technical assistance for improving youth nutrition in the existing food landscape. Part of Christina’s role focused on the inclusion of food cultures that were less visible in existing sustainable urban agriculture initiatives.

“There was a meeting when I realized that the nearby Puyallup Tribe had largely been left out of the planning conversation. So I looked at strengths-based approaches to replicate the success of Indigenous-led programs and events, like Na’ah Illahee Fund’s Ya-howt permaculture certification program and the Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ symposium,” she said. “ This project was an opportunity to bring traditional ecological knowledge into school-based nutrition programs and community spaces, and to promote interactive and place-based knowledge transfer between youth and elders.”

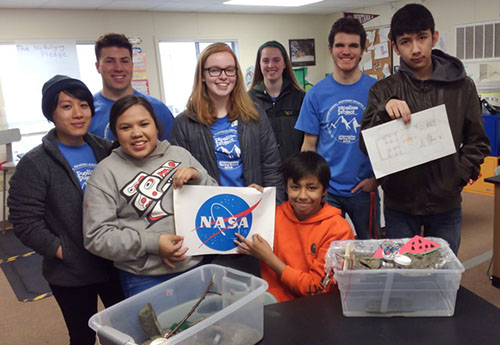

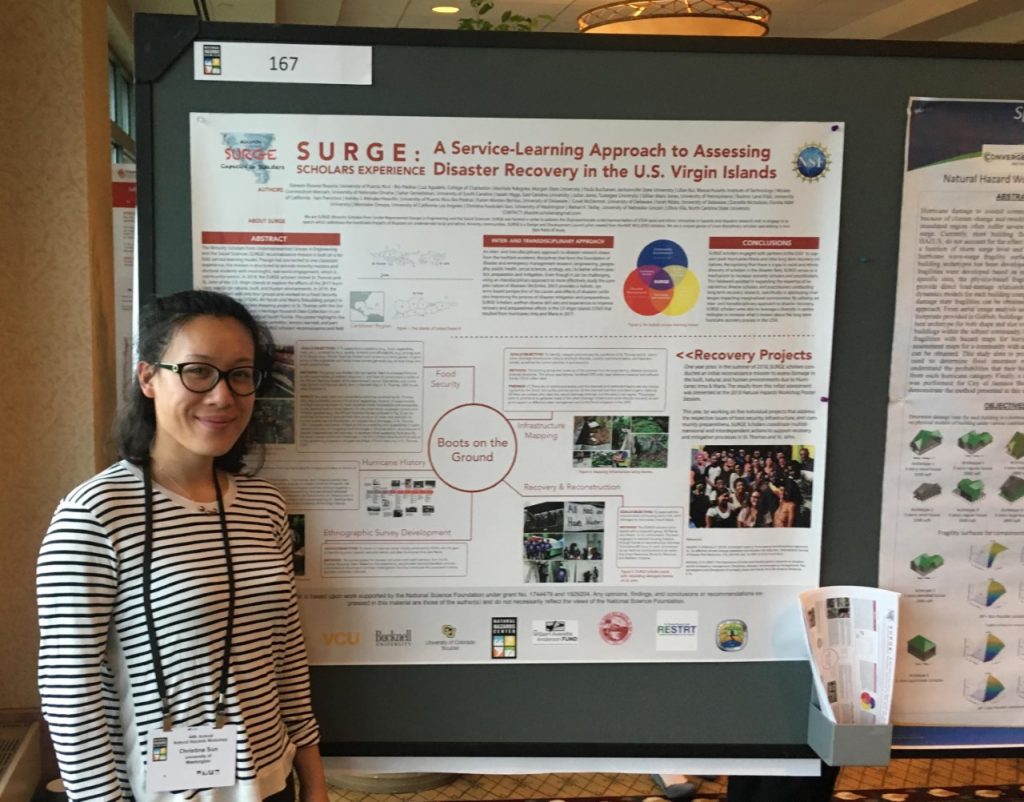

Over the past year, Christina, an aspiring disaster epidemiologist, expanded on her work in food insecurity with the Scholars from Under-Represented Groups in Engineering & Social Sciences (SURGE), a National Science Foundation-funded pilot program. SURGE aims to increase the number of STEM students of color entering hazards and disaster research via service-learning and professional opportunities for vulnerable communities in the U.S.

The cohort traveled to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to help with projects supporting the long-term recovery of St. Thomas and St. John, both heavily impacted by recent hurricanes. Following an assessment of food shortages in grocery stores and supermarkets, the team designed small indoor gardens to grow fruits, vegetables, and herbs. Other projects included adapting FEMA’s Survey123 template for use in longer-term recovery assessments, developing a timeline to identify areas most prone to damage during hurricane season, and mapping existing infrastructure to evaluate the resilience of buildings and small farms against future storms.

The issues of human security faced by these communities are not unlike the ones experienced today by Pacific Islanders, who are already feeling the effects of climate change and rising sea levels. Christina’s early interest in water security and water resources management in Pacific Small Island Developing States has led her to concurrently pursue a graduate certificate in Climate Change and Health.

“Pacific Islander communities are already feeling the impact of climate change,” she said. “Rising sea levels have resulted in saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers, reducing agricultural productivity and the land’s capacity to support existing ecosystems. This poses more stress on traditional Pacific Islander food systems, putting these communities at a higher risk of obesity and nutrition-related health problems. This is where the importance of public health data comes in for these communities”

In June, Christina received a travel grant from the Department of Epidemiology to travel to Aotearoa (Maori name for New Zealand) for the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA) annual meeting, where she spoke on a panel about the future of research for Indigenous communities. This meeting brought together Indigenous researchers from around the world, many of whom were interested in learning more about epidemiologic methods and tools to harness data to help their communities.

“When looking at public health practice through our values, the field has not exactly addressed the health burden experienced by Indigenous and minoritized communities,” Christina said. “There is a need for applied epidemiology, in particular, to reconsider concepts like generalizability and statistical power for smaller populations. It is not enough, nor is it helpful to say, there is ‘insufficient data’ and ‘statistically insignificant’ information in epidemiologic studies pertaining to minorities.”

Christina left the conference with a reaffirmation of the strength and rigor of Indigenous knowledge, and how it is produced and shared. Not only that, she also left with a determination to continue to learn how to data tools and resources to advance research by, with and for Indigenous peoples.

With this goal in mind, Christina will start a second master’s program in computer science at Northeastern University next year. She plans to combine her epidemiology expertise with machine learning, finding ways to increase access to large datasets in order to improve health outcomes for Indigenous populations around the world.

“I believe that machine learning is one of the tools we can use to help make data more accessible to the next generation of Indigenous researchers,” Christina said. “This is an opportunity to bring together data generated from across many disciplines, to address the Digital Divide, and to challenge histories of depopulation, displacement, and research ethics. It is time to put Indigenous-generated knowledge back in the hands of the communities they were intended to heal.”